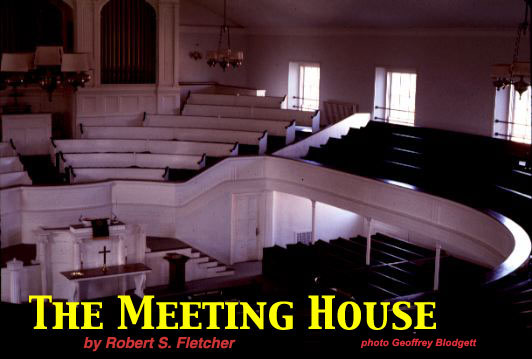

Only one building still survives from the days of Oberlin's youth, but it is the one above all others which we would wish to keep. We value it for its intrinsic qualities -- for its simplicity and sincerity, its perfect balance, its economy of material and ornament, and the wholehearted way in which it hugs our tough clay soil.

We treasure it, too, because of its historic significance. It was the center and capitol of the community, and it was the most important College building. It housed the church, but it was not the church -- it was the Meeting House. It was the gathering place for all -- mechanics, professors, farmers, students, housewives, merchants, all the members of a fully integrated society. It stands as a reminder of the remarkable unity of high moral purpose which once existed here.

The cornerstone was laid on June 17, 1842. It is not difficult to reconstruct the scene. -- Here and there are heaps of yellow earth from the fresh-dug cellar, blocks of rough-quarried sandstone, perhaps some great oak floor-beams and straw-nested bricks. Quite a crowd gathered. The women wear full skirts, coal-scuttle bonnets and fringed shawls, and the men are dressed in black broadcloth and high, choking, white neck-cloths. The little girls are absurd replicas of their mothers whose sleeves they firmly clutch. Many of the boys are perched on the top rail of the "worm" fence that bounds the square across the road. A spotted cow wanders down Main Street nibbling at the roadside buttercups and attracts no particular attention. Dust rolls up from the wheels of an approaching farm wagon. Then the tall, erect figure of Professor Finney (who is also the pastor) mounts an improvised platform and his uncovered head glints in the early summer sun. All reverently bow as he leads in long and impassioned prayer. A hymn is sung (specially written for the occasion), and the cornerstone is "well and truly laid." The townspeople drum away along the plank walks toward their homes. The students stream across the cow-paths of the square to Tappan Hall and Ladies' Hall.

The Oberlin religious society known as "The Congregational Church of Christ at Oberlin" was formed in 1834, and it was the only church in Oberlin until the fifties. All of the College faculty and their families and practically all the other residents were members. Religious services were held at first in various College buildings or in the big, circular tent which was erected for the purpose near the center of the square. All students were required to attend. The preaching was done by members of the College staff as a part of their regular duties. Father Shipherd, the Founder, was the first pastor, succeeded by Professor Finney. But Mr. Finney was often absent, preaching in the East or in England, and then the pulpit would be filled by Professor John Morgan, Professor Henry Cowles or Professor Henry E. Peck. The choir, which was identical with the student musical association, was directed by the professor of Sacred Music.

At first all available funds had to be used for dormitories and classroom-buildings but, as the student-body and the population of the town grew larger, the need for a more adequate place of worship became increasingly pressing. There were no auditoriums large enough for the Sunday congregations nor for the Commencement crowds, and the tent was a poor make-shift, totally unsatisfactory in inclement weather. Finally, in February, 1842, the church society voted to "proceed forthwith to take measures for building a meeting house." The cornerstone, as we have seen, was laid in the following June, but construction was not completed until late in 1844.

The Meeting House was built like a mediaeval cathedral with the offerings of material and labor from the people of the community and their friends abroad. We really have no idea how much it cost because very little money was involved. Oberlin masons, teamsters, blacksmiths, tinsmiths, carpenters and cabinet makers donated part or all of their time. Others gave bricks, stone, timber, hardware and paint. The acknowledgements of gifts list money (usually a dollar or two from each person) and also twelve pounds of nails, a hat, a cheese, four bushels of apples, a barrel of flour, a one-horse wagon, and two cows from residents of Medina. Most of these articles, of course, would have to be sold or exchanged in order to apply them on the building. This was not impractical, for old records show that, on one occasion, the College paid "one hat" to have a stone quarried and delivered.

The designing was an amazing demonstration of practical democracy. An architect's plan was contributed by a Boston friend, but it was liberally revised by vote of the church members. At one meeting they voted, for example, that the tower should follow a certain drawing in "Benjamin's Architect." The actual construction was supervised by a committee which, fortunately, included Deacon Thomas Porter Turner, an experienced house-carpenter from Thetford, Vermont.

There were two preaching-services every Sabbath one in the morning and one in the afternoon. All the people came, Negroes and whites, from every part of town -- one man brought his wife in a wheel-barrow. They filled the house to the doors. The families sat in their assigned pews betweent he great black stoves that stood sentry on either side near the windows. The students crowded the circling balcony. The sermons might last an hour or two, prayers perhaps half as long. The bass viol or the organ (after 1855) accompanied the hymns sung from Mason's and Hastings' song books.

The Oberlin Musical Association, which later became the Musical Union, gave its concerts in the Meeting House. There the first oratorio was performed in 1852, and in two evenings five hundred dollars was taken in at twenty-five cents a person. The musical accompaniment was furnished by a piano, a melodeon, two flutes, two violins, a 'cello, a violone, a horn and a drum. One year Lowell Mason led a musical convention in the Meeting House, and choir leaders from all over northern Ohio came to Oberlin to profit by his instruction.

Commencement exercises were held there from 1843 when the building was still unfinished. The walls were decorated with greenery, and sawdust was spread up and down the aisles. (The spreading of the sawdust was a special Junior-class ceremony.) The Senior Class sat on the platform, the young ladles in white, often with blue sashes. One after another each came forward and read an essay or delivered an oration on such subjects as "Moral Heroism," "Right the Basis of Law," "The Dawn of Mental Freedom," or "National Responsibility." Parents and other visitors came from far and near; both the governors of Ohio and Michigan were present in 1859.

No one ever thought of there being anything sacrosanct about the building. Any meeting which Oberlinites would want to attend might be held there. Bayard Taylor lectured in the Meeting House on "The Arabs, their Character and Customs," and commented flatteringly on its acoustic qualities. Others who lectured there were Horace Greeley, Carl Schurz and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Long before the movies, children and adults flocked to the Meeting House to see displays of panoramic paintings - - in 1853 one of Niagara Falls. Some college classes met there and, for a while, the building housed one of Oberlin's public, common schools. It was the first fire station. The old hand-operated fire-engine was kept in the basement for a number of years, and the fire laddies drilled in the yard.

In 1859 twenty-one Oberlin citizens were incarcerated in the Cuyahoga County Jail at Cleveland to await trail for assisting in the escape of a fugitive Negro slave. Among them were James M. Fitch, superintendent of the Sunday School, and Henry E. Peck, professor of Moral and Mental Philosophy. In July all but two of the prisoners were released and returned in triumph to Oberlin. The welcoming ceremonies were held, of course, at the Meeting House. It was already filling up when the procession from the depot came in sight: the Citizens' Brass Band in the lead, the fire companies in uniform, the freed Rescuers and the reception committee of students and citizens. All the bells were rung and cannon were fired every few minutes. Garlands of flowers were heaped upon the heroes' shoulders as they passed in the front door and down the aisles to the platform amid deafening cheers. Father Keep, dean of trustees, presided. The musical association sang the Marseillaise. Everybody made speeches. It was just before midnight when the Doxology was sung and the benediction pronounced.

On April 17, 1861, four days after the surrender of Fort Sumter, a great Union Rally was held at the Meeting House. There were speeches by Professor Peck and Professor James H. Fairchild, by Mr. Fitch and by Oberlin's distinguished Negro Lawyer, John M. Langston. The Musical Union sang the "Star Spangled Banner." The next Sabbath, during the reading of the notices, Father Keep arose In his pew to ask if there was any more news. The week following, the first of a series of companies of Oberlin student- soldiers was organized and soon marched away.

Though for Lincoln and many in the North that war of the sixties was a war for the Union, to Oberlin it was always a fight for freedom. "In this colilsion," wrote Finney, "the cause of the slave is that of humanity, of liberty, of civilization, of Christianity." Naturally, the Emancipation Proclamation was received with complete approval and great enthusiasm. In April, 1863, the commandant of the Negro refugee camp at Washington addressed a large audience in the Meeting House by invitation of the Students' Missionary Society. The challenge there presented drew hundreds of Oberlin men and women to the conquered portions of the South as educational missionaries among the freedmen -- and resulted in the re-establishment of Berea and the founding of Talladega and Fisk.

Finney is gone. Professor Peck died long years ago of yellow fever in Haiti. Sunday-School Superintendent Fitch is near forgotten. One and all, the men and women of those days - - faculty members, towns men, and the thousands of students who found here moral and mental training, stimulation and inspiration -- they are gone. But thevoice of Oberlin-in-its youth still echoes from the walls of the old Meeting House. It is a decisive voice with no captious quaverings, a voice of hope and not of cynicism, a brave voice, a fighting voice, a voice that speaks in no uncertain terms for decent justice for all humanity, for a righteousness unlimited by convenience, for the brotherhood of all races and all colors of mankind. It Is not a voice of consolation but a voice of alarm. It cries out in indignant anger against all tyrants and all forms of slavery.

Robert S. Fletcher was Professor of History at Oberlin College from 1927 to 1959. He is the author of A history of Oberlin College from its foundation through the Civil War, published in 1943 by Oberlin College.